Harrow Industrial Stories – Kodak

The research for our recent report “Harrow Industrial Stories” on the local economy of the London Borough of Harrow’s industrial estates uncovered a fascinating collection of businesses from the extra-large to the extra-small. We have discovered that there is actually very little known about the businesses on London’s industrial estates. What is known is mostly based on high-level statistics. The industrial estates are often not very visible, accessible or integrated into our neighbourhoods. More importantly, though, the research demonstrates that the most important factor for local economic development are the entrepreneurs and employees, the people, who make up these businesses.

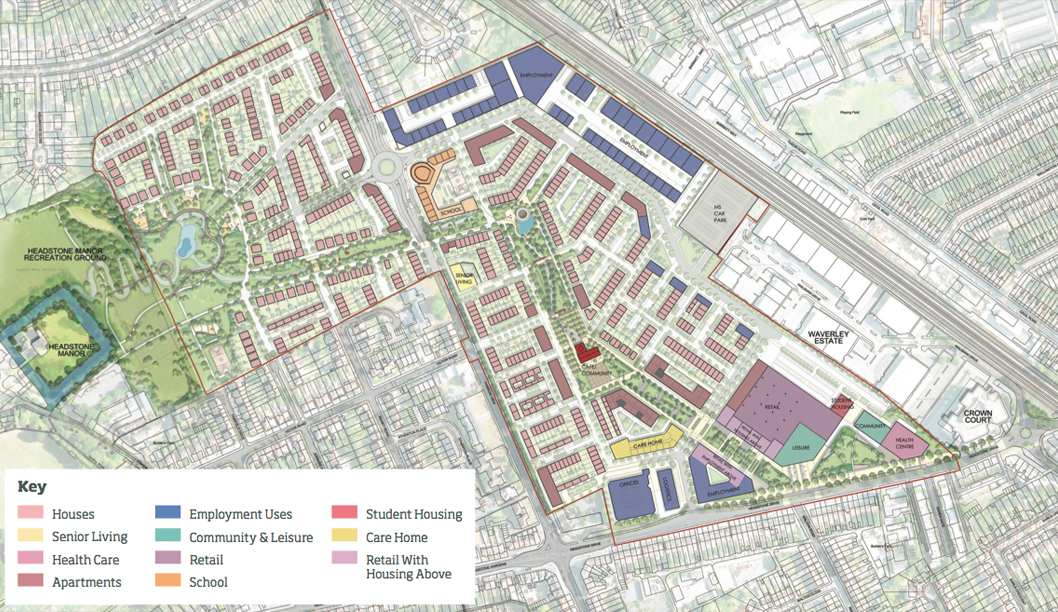

This is the story of Kodak, the oldest and largest business in Harrow. In recent years a large part of the site has been cleared of redundant buildings and sold to one of UK’s largest developers, Land Securities. Outline planning permission has been granted this year to the developer for a masterplan which also included the land which is not (yet) owned by the developer and still has a working factory on it. Kodak, an American company, ran into serious financial problems a few years ago and will now come back out of bankruptcy protection and to be restructured. The factory is still producing colour photographic paper and shipping it around the world, however demand is in decline because people increasingly prefer to see photos on their phones and tablets.

At the heart of the factory five layers of light sensitive emulsion are applied to rolls of paper at high speed creating the colour photographic paper. What makes the factory peculiar is that a lot of the process happens in complete or partial darkness due to the light sensitive nature of the emulsion. Kodak was founded in 1889 and made photography available to a wider public by selling inexpensive cameras and making large margins by developing and printing people’s photographs. A year later Kodak bought seven acres of farmland in Harrow because of the availability of good groundwater. The factory was up and running in 1891 developing and printing customers’ photographs.

A massive photographic archive documents the fascinating history of the factory, its processes and people. The archive was donated by Kodak to the British Library in 2009 where it is being made accessible. One of the earlier photographs shows employees using sunlight to print negatives in Building 1’s upper gallery. Chickens were kept at the factory to supply the egg white to coat the contact printing paper. The factory expanded as Kodak led the photographic market. A Kodak engineer even developed the very first digital camera, however the idea did not get anywhere because Kodak’s business was based on selling film. It would seem that it was this type of inflexible business practices, not necessarily the shift to digital photography, which brought down the company.

In its heyday the Kodak factory in Harrow employed 6000 people, today less than a thousand remain. Three teams work on 12 hours shifts to keep the production line running day and night, one working, one resting while the other has time off. Bob, the site manager, has been working at the factory for over 30 years and knows the whole production process inside out. His brother and sister had worked at the Kodak factory before him. During his time at the factory, he has seen the Kodak football club, the Kodak museum and some of the original factory buildings disappear. What the future holds for what is left of the factory is currently unknown.

Large factories such as Kodak are disappearing and the land they occupy tends to be used for residential developments due to the large demand for housing. At the same time there is also a increasing number of small industrial businesses with a growing need for space. To create sustainable urban developments and local economies, Harrow and other London Boroughs need to take concrete steps to support small industrial businesses by making sure that there is affordable space for them in their local areas so that they are not pushed and priced out of the city by residential development. Both central and local government should support the provision of affordable small business space as well as affordable housing to help local economic growth.